Introduction

The word ‘city’ is derived from the French word ‘cité’ meaning town. Around the sixteenth century, the idea of city came to represent the character of life in a neighborhood, the feeling people harbored about neighbors and strangers and attachments to place.[1] I’m personally more fond of the cite’s anthropological consciousness; which describes it as a phenomenon based on space or place, but subject to varying interpretations. Early times cities started as economic hub, social activities, and center of power/governance; today scale, function, and smartness are varying to contexts. The perception of city has evolved over the years and I wonder how can a city be defined. What are the aspirations while living in a city. How does one explain the nature of urban?

Human settlements evolve in diverse geographies, and existence of dense human settlements in good enough natural landscapes is a simple palette to start explaining the urban life. Historically, humans have created cities to foster community, a more cooperative atmosphere, resource sharing, and work together to sustain the common good. Lewis Mumford shared this same idea in his book ‘The City in History’[2] and further adds that the first city planning encouraged innovation and technical advancement. During that time, everyone wanted to succeed and contribute to the city’s growth, so they worked together to develop new ideas for how to make their lives simpler collectively. We used to do this and have lost this sense of cooperation in our ways moving forward in centuries. Measures in calculating the city’s growth were often misguided in the past. For instance, Jane Jacob’s ‘The Death and Life of Great American Cities’ stood to a place in history for its human centric and community oriented sense of ownership for the city.

The urbanism and metropolitan areas that we see today have come a long way, and in this paper I’m attempting to define the relevance of design as a tool for encouraging collaboration among individuals. I also try to showcase the potential of using design as a tool in creating policy implications for altering urban administration in providing justice in cities.

The paper is divided into two sections, broadly. Here in the first part of the paper explains the role of design as a tool and participation in city planning; followed by explaining the theoretical and literature study about design in politics, and design as tool for participation. In the second part, various aspects of involvement in design in planning projects are explained using personal experiences from the past projects worked and observed closely. I conclude by using design, participation, and justice as three lenses to comment on the three case studies described.

Using Design as a Tool

Design plays an indispensable role in cities, which is beyond urban design and spatial planning. The paper defines design from the policy and political angle. It explores the journey of use of design such that its methods and practices are being applied to urban planning and public administration. In the modern cities, design methods and designers are mobilized to address the governmental problems.[3] Practitioners have discovered there is no single precise solution to the numerous concerns that cities face over the years; rather, there are collaborative ways involving experimenting and planning methodologies. Collier and Gruendel (2022) made a strong impression on the developing role of design techniques in large-scale urban projects and explained how they relate to fundamental issues with contemporary politics. Analyzing design in governance is similar to analyzing political processes in large scale projects, where the focus is on organizing argumentation, making decisions on complicated, big-picture issues, and defining the place of expert knowledge. Thus, design in politics goes beyond the creation of physical objects.

City planning and public sector design are frequently done in collaboration with architects, planner and studio-based design practices, where they use an iterative design process. In this design processes, the studio and agency goes back and forth on revising the projects. Beyond the studio, community design workshops, spatial studies, brainstorming sessions, etc. are conducted to further their work and promote the importance of design in urban administration. However, citizens are now challenging these traditional approaches to problem-solving because they fall short of truly comprehending the “wicked situations”. In their book “Dilemmas in a General Theory,” Melvin Webber and Horst Rittel define the phrase ‘wicked situations’ – as situations that are singular, lack a clear solution, and have solutions that cannot be categorized as good or bad, true or untrue, finite, or immediate. Furthermore, it was unable to clearly distinguish between the political and administrative components of goal-setting and problem-solving. By its very nature, planning was political, and politics were only able to emerge as issues and potential solutions were uncovered throughout the planning process. Wicked problems never had an ideal solution, rather, they are constantly “re-solved” (p. 160). Collaboration, transparency, and participation are only a few of the many strategies that must be used to address the complexity of issues in the public sector. Contextualized approaches are using these instruments, despite their limitations, to influence the democratic process. Another query was how to develop novel paradigms for the role of technical experts in democratic decision-making.

The varying fields of planning and urban design have a significant role in addressing these modern day challenges. The experts are engaging in conversation with communities along with modern digital tools to best tackle the issues on social justice, inclusion, environment challenges and curating new methodologies of design to engage government with public. For example, large scale urban projects are dealt with interdisciplinary expert teams, ensuring the new modes of people participation alongside new design approaches. Public voting on commissioned large scale projects, design competitions, engagement of local stakeholders are eminent part of these processes. To emphasize, design of both the microscale spaces and macro space planning are equally important in shaping the future cities.

Why participation?

The definition of a democratic planning process and how one might define their right to the city date back a long way. Claims to ‘the right to the city’ have emerged as significant discourse in social movements all over the world, both theoretically and in practice. Henri Lefebvre, in The Urban Revolution, argued for the emergence of the city as a social as well as economic space through participation. The conceptualizations by Lefebvre[4] and Harvey[5], critically look at changes in planning policies as a collective right. The right to the city is not merely a right of access to what already exists, but a right to change it. The right in remaking and creating qualitatively different kind of urban society is right to humankind. But how do we construct a socially just city? Can participatory planning process, with collaboration and transparency, bring in changes? How do they vary contextually?

Margo Huxley, planning theorist, demonstrates how certain spatio-temporal circumstances led to the conceptual category of “participation” emerging throughout the history of planning theory and practice. These include the Civil Rights movement, campaigns by local activists, and the general emergence of notions of community that challenged the inclusive potential of the “liberal oligarchies” of representative democracy and the state in these countries.[6] The 1960s political upheaval in the US and UK that demanded more community involvement and local government autonomy are also included. Planning, who does it, and how they do it are all essentially related to participation. Therefore, their identities retain their connection to one another as analytical and practical frameworks.[7]

There are numerous instances of institutionalizing different types of participatory planning into governance. I review recent literature on participatory planning in global south cities and urban inequality, housing concerns, urban social movements, and other issues might be addressed by drawing comparisons.

The participatory aspects of planning are challenging, unfamiliar and mandated differently in varying contexts. Upon analyzing a constitutionally mandated urban policy model in Brazil, Caldeira & Holston (2014)[8] noted that there is no assurance that popular engagement would result in social fairness or respect for constitutional rights. A key objective of democratic urban reform was to institutionalize participation as a means of enacting democratic principles of municipal governance and greater social justice. When involvement is possible, how should we evaluate if this democratic process gets translated into urban policies? By examining the politics of participation in Bangalore, the author of Sundareshan (2016) illustrates a different type of institutional fragmentation and failure in Indian cities. Here, the planning scholars examined the spaces of interaction rather than the domain of the state. Likewise, Sundareshan & John (2021)[9] demonstrated distrust, anger, and fear in the participatory boundaries, particularly in the post-colonial urban development. Along with caste and class divisions, corruption, state ideologies, and other factors, emotions are a major factor in the creation of urban planning processes and outcomes. In India, dynamic participation shapes the vernacular governance and this goes beyond the usual state-society binary framework. For instance, in governance framework, ‘the state’ invites ‘society’ to participate in the state’s ‘terms’.

Design is political, and design also has its own politics. From Nancy Fraser’s[10] pivotal work on justice, we understand the three dimension of justice. The economic dimension of distribution, the cultural dimension of recognition and the political dimension of representation. In this instance, first is the problem of class structure of society that corresponds to economic dimension of justice, Second case the problem is the status order, which corresponds to its cultural dimension. And encompassing in all these are the political dimension of representation inside the city.

Here I want to comment, designing large scale public projects have the potential to deliver or deny these forms of justice. However, the fundamental form of justice is parity in participation and using well-designed and informed planning process participation can be ensured, opening up the opportunity for serving justice. How do we design just cities ? Susan Fainstein[11] develops an urban theory of justice and discusses the issue of justice with cities with three governing principles – equity, democracy, and diversity. Role of underrepresented groups, redistribution of goods, service and broader participatory role in policymaking are key aspects. Edward Soja[12] explains that spatial justice involves fair and equitable distribution of space of socially valued resources and opportunities to use them.

“Locational discrimination created through the biases imposed on certain populations because of their geographical location is fundamental in the production of spatial injustice and the creation of lasting spatial structures of privilege and advantage” (Soja, 2009)

Case Studies

In the following discussion, various projects are looked from a justice lens, where participatory planning approaches are used. Both macro and micro level study is relevant, but in this instance participatory approaches in microscale, that is from an individual urban project are explained. Here, I give my reflections on the projects I worked at the “Recyclebin” multidisciplinary urban practice in Trivandrum, India. The following case explore urbanism from a people’s engagement perspective, as well as how design altered to accommodate distinct local governmental missions.

Kerala, an Indian state, is regarded as a socially democratic development state among numerous transformational democratic politics in the global south. In Kerala’s towns and cities, local democracy and decentralization strategies are well-liked. The political competition has compelled the left aligning parties to collaborate closely with civil society organizations and social movements, creating political movements in support of transformational democratic politics at the local level. In addition, it should be noted that Kerala still fall short in the high expectations of democratic involvement in planning and urban development. The following examples will narrate three collaborative design attempts in local level.

1) Museum of Habitual Errors

Trivandrum city banned single use plastic on March 01, 2017, and the Museum of Habitual Errors was the name given to the public exhibition that was part of the awareness campaign. An exhibition that narrated the journey of waste in an everyday life. The local authorities have also displayed alternative sustainable materials as part of the campaign.

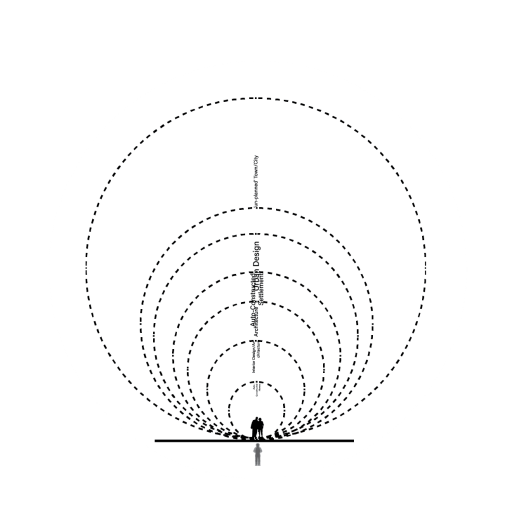

Our team of designer and urbanists were invited to conceptualize the museum. The physical design was inspired from the location and existing site landscape. (Image 1) The museum was a temporary structure built in a public park in the heart of the city and most importantly constructed out of 70,000+ trash PET bottles. The complete process of material collection, construction, and documentation was a public participatory effort. It was a community event that attracted volunteers from the area as well as college students, NGOs, and zero waste activist groups. Plastic pens, papers, cups, bottles, straw, food containers, sanitary napkins, e-waste, etc. were the exhibits of the habitual errors, (common day’s waste).

The mayor of the city corporation assembled a group of local health inspectors and personnel to solicit design and conceptual input from the design team. They were enthusiastic about the approach, as it was quite new to the bureaucratic system. The novel approaches to participatory design gave the new city policy (of plastic ban), an unusual appeal to the traditional media coverages.

“Waste stinks !! But is it the waste in the backyards, or is it the backyard in us that stinks ?

It’s a world full of inner backyards, and waste is a mere expression of the same.

If waste does, We do stink!!

Museum of Habitual Errors explore the stinking relation we have with our world.

Waste is portrayed as a phenomenon of collective existence, to a fingertip association of day to day scale.

Here waste transforms from mess to our habitual errors.”

- Ganga Dileep C, the studio’s chief designer and urbanist.

Volunteers sorting and threading the waste plastic bottles. Photo credits – Recycle Bin team

2) Toilet tales

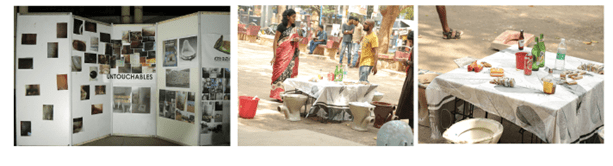

Recycle Bin studio describes Toilet Tales as – “A holistic research on the phenomenon of public toilets”. In the light of the journey, in November 2017, Toilet Tales by studio Recycle Bin was launched with the goal of analyzing, enhancing, and quantifying Kerala’s toilet culture. The campaign was initiated with a study of the toilets in Trivandrum, the capital city of Kerala. The initiative was sparked by a study of the restrooms in Trivandrum. Various types of public toilets linked public comfort stations transit, religious, community and recreational were documented and studied. The majority of the toilets had unsanitary conditions, based on the study of 50 toilets. The toilet study was conducted by a group of volunteers, students, and activists motivated in the mission. Image 2 shows the spatial study done for the public toilet and the challenges experienced while using the space is discussed.

One step ahead with this study, a toilet (kakkoos) app was introduced in response to the push for cleaner and more easily accessible public restrooms. The software could find and map restrooms, and detailed information about the restrooms, such as type, gender, amenities, economy, usability, etc., could be added. The database also had the potential to inform future studies. Upon the survey there were many unused, dilapidated and locked or abandoned toilets. Among the so-called functioning once, people hesitated to use them because of privacy, hygiene, location, and lack of facilities for accessibility, and support for child, or menstruating women. The research identified three main aspects that dictate the proper functioning and success of public toilets – Public behavior, toilet character and governance.[13]

Later on the project has expanded to Chennai via team Recycle Bin and an extended version of toilet mapping, study, expo, toilet fellowship[14] and international toilet festival were conducted in 2022. I’m glad to be part of the event virtually in sharing insights on how to document public toilets. The current version of the Toilet apps has more than 15,000 toilets mapped to the last detail with photos. The ongoing research traces three major aspects relating to public toilets:

- The Individual – A question of toilet literacy. The toilet stands as a testimony of the culture and mindset of a society, which roots itself in the behavior of each individual using it.

- The infrastructure – A question of image. The built structure and its facilities being the tangible aspect to which people relate, the image put forth by it is instrumental in deciding its equitable usage.

- The governance – A question of ownership. Maintenance and timely monitoring of toilets often pose a conflicted sense of ownership among the users, the toilet keepers and the providers.

Sketches on the toilet spatial study & execution. Credits: Meenakshi Meera

Community participation event at Trivandrum, 2017

3) Carbon Neutral Meenangadi, Wayand

The Meenangadi panchayath of Wayanad aimed to become the first carbon-neutral village. They planned to achieve this by: conserving and expanding its forest and biodiversity, reducing its carbon emission too drastically from household, transportation and industrial sectors, conserving its oil and water, practicing organic agriculture, reducing and recycling waste, and preparing to tackle climate change with best practices for sustainable development.

The over project had different stages of work, like transit walk, generating conceptual thread for complete master plan, participatory workshop with communities, transit station and resource park to be designed as an energy efficient model. The bottom up responsibility model was developed with shared power and responsibility. The preliminary study was based on physical, social, infrastructure, agroecosystem and livelihood classifications. As a team, we used games and engagement tools to explain the ideas behind carbon neutrality. This concept was strange yet familiar to the agrarian community’s way of life. The community, stakeholders, political organizations, and technical experts were actively involved in the development of social schemes and planning policies, which provided valuable insights. The nonprofit organization – Thanal, played an important role in building long term relationship with the people and bringing expert groups together. The report[15] explains more details. In this instance, democratic planning component was integrated into the process by the elected political parties.

Photos showing community participation event at Meenagadi, 2017; Images from left clockwise – agricultural topography changes and people’s relation to water; travel distance mapping; carbon abacus explaining neutrality concepts to students; tracing history of local practices.

Discussion & Comments

The projects/cases here are examples of how design can create opportunities to build inclusive public planning processes and ensure participation at large. These forms of engagement go beyond the electoral politics of parties and reaches the realm of justice through proper informed design practices.

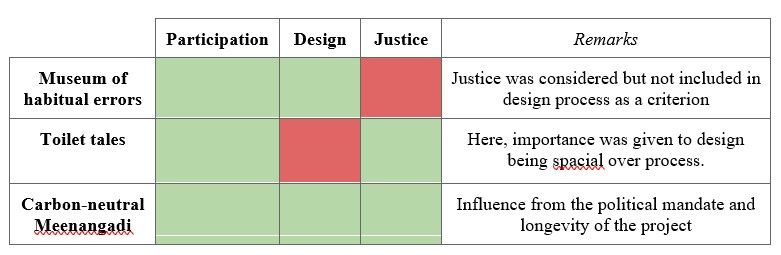

Closely observing the projects through three lenses –

- Participation (whether there was community engagement in defining the project, taking inputs that can translate or inform the final design, policy)

- Design (whether it was responsive design strategies or creating inclusive space or adding new designer approaches within governance)

- Justice (whether the project had strong approach on justice, economic, cultural and political)

Color codes – green shows visible effort made in corresponding columns and red represent no visible efforts made involvement in three lenses.

In the Museum of Habitual Errors, there was community participation as well as informed design approaches within city governance. The architects and designers team deliberately took clues from the site and overall concept of public awareness in the issues of waste, while curating/designing the museum. As I reflect, I can see layers of inherent justice flowing into it, like the decision on choosing materials and creating an experience that opens the public eye towards environmental justice. However, conceptual during the design process it was not included as a parameter with discrete outcomes.

In Toilet Tales, there was participation and justice angle is very strong. As the project addressed cultural and political conversations around public toilets, the justice angle was introduced in the design process itself. Predominantly the justice of recognition, of who can access the toilet and who is denied to access. Community participation, organized public towards this important cause. In the later phases, the team has done design explorations to create a model toilet, which could be prototyped for public spaces. Hence, spatial design was added in the later phase.

In Carbon-neutral Meenangadi, the scale and longevity of the project was comparatively big and all three lenses of participation, justice, and design play a part in it. This was also due to the direct political involvement to ensure goodwill across the village through the face changing initiative.

As mentioned, using these three concepts in varying combination can give valuable insights during and post urban planning projects.

Limitations

The essay here was written as an extension of ideas from past practice and ongoing research explorations. I strongly believe that this can be bettered using well-defined qualitative methods for designing these case studies. I acknowledge the limitation and bias from self-reporting.

[1]Sennett, R. (2018). Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City (First American Edition). Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

[2]Mumford, L. (1968). The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. Mariner Books.

[3]Collier, S. J., & Gruendel, A. (2022). Design in government: City planning, space-making, and urban politics. Political Geography, 97, 102644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102644

[4] Lefebvre, H. (1968) Le droit à la ville. Paris: Éditions Anthropos.

[5] Harvey, D. (2008) ‘The right to the city’ New Left Review

[6] Huxley, M. (2013) ‘Historicizing Planning, Problematizing Participation’, International Journal of Urban

and Regional Research, 37 (5), 1527–41.

[7] J,Sundareshan (2016) The politics of participation in the land-use planning of Bangalore, India

[8]Caldeira, T., & Holston, J. (2014). Participatory urban planning in Brazil. Urban Studies, 52(11)

[9] Sundaresan, J., & John, B. (2020). Emotions, Planning and Co-production: Distrust, Anger and Fear at Participatory Boundaries in Bengaluru. Urbanisation, 5(2), 140–157

[10] Fraser, N. (2010). Scales of Justice: Reimagining Political Space in a Globalizing World (New Directions in Critical Theory, 31) (Reprint). Columbia University Press.

[11] Fainstein, S. S. (2010). The Just City (1st ed.). Cornell University Press.

[12]Soja, E. (2009) The city and spatial justice. Spatial justice

[13] https://toilettales.in/images/Report.pdf

[14] https://toilettales.in/fellowship.html

[15] https://thanal.co.in/uploads/resource/document/carbon-neutral-meenangadi-assessment-recomendations-87546380.pdf